From farm to pharmaceutical,

diesel truck to dinner plate, pipeline to plastic product, it is

impossible to think of an area of our modern-day lives that is not

affected by the oil industry. The story of oil is the story of the

modern world. And this is the story of those who helped shape that

world, and how the oil-igarchy they created is on the verge of

monopolizing life itself

www.corbettreport.com/episode-310-rise-of-the-oiligarchs

Parts of the oil story are

well-known: Rockefeller and Standard Oil; the internal combustion engine

and the transformation of global transport; the House of Saud and the

oil wars in the Middle East.

Other parts are more obscure: the

quest for oil and the outbreak of World War I; the petrochemical

interests behind modern medicine; the Big Oil money behind the “Green

Revolution” and the “Gene Revolution.”

But that story, properly told,

begins somewhere unexpected. Not in Pennsylvania with the first

commercial drilling operation and the first oil boom, but in the rural

backwoods of early 19th century New York state. And it doesn’t start with crude oil or its derivatives, but a different product altogether: snake oil.

“Dr. Bill Livingston, Celebrated

Cancer Specialist” was the very image of the traveling snake oil

salesman. He was neither a doctor, nor a cancer specialist; his real

name was not even Livingston. More to the point, the “Rock Oil” tonic he

pawned was a useless mixture of laxative and petroleum and had no

effect whatsoever on the cancer of the poor townsfolk he conned into

buying it.

He lived the life of a vagabond,

always on the run from the last group of people he had fooled, engaged

in ever more outrageous deceptions to make sure that the past wouldn’t

catch up with him. He abandoned his first wife and their six children to

start a bigamous marriage in Canada at the same time as he fathered two

more children by a third woman. He adopted the name “Livingston” after

he was indicted for raping a girl in Cayuga in 1849.

When he wasn’t running away from

them or disappearing for years at a time, he would teach his children

the tricks of his treacherous trade. He once bragged of his parenting

technique: “I cheat my boys every chance I get. I want to make ’em

sharp.”

A towering man of over six feet

and with natural good looks that he used to his advantage, he went by

“Big Bill.” Others, less generously, called him “Devil Bill.” But his

real name was William Avery Rockefeller, and it was his son, John D.

Rockefeller, who would go on to found the Standard Oil monopoly and

become the world’s first billionaire.

The world we live in today is the

world created in “Devil” Bill’s image. It’s a world founded on

treachery, deceit, and the naivety of a public that has never wised up

to the parlor tricks that the Rockefellers and their ilk have been using

to shape the world for the past century and a half.

This is the story of the oiligarchy.

PART ONE: BIRTH OF THE OIL-IGARCHY

Pennsylvania Rock Oil Company

Titusville, 1857. A most unlikely

man alights from a railway car into the midst of this sleepy Western

Pennsylvania town on the shores of Oil Creek: “Colonel” Edwin Drake.

He’s from the Pennsylvania Rock Oil Company, and he’s here on a mission:

to collect oil.

Like “Dr.” Bill, Drake isn’t

really a Colonel. The title is bestowed on him by George Bissell and

James Townsend, a lawyer and a banker who started the Pennsylvania Rock

Oil Company after they discovered they could distill the region’s

naturally occurring Seneca oil into lamp oil, or kerosene. Drake is

actually an unemployed railroad conductor who talked himself into a job

after staying at the same hotel as Bissel the year before. Calling him a

Colonel, it is hoped, will help win the respect of the locals.

The locals think he’s crazy anyway. Seneca oil is indeed plentiful,

bubbling out of seeps and collecting in the creek, but other than as a

cure-all medicine or grease for the local sawmill’s machinery, it’s

hardly seen as something valuable. In fact, it can be a downright

nuisance, contaminating brine wells that supply Pittsburgh’s booming

salt industry.

Still, Drake has a task to

complete: finding a way to collect enough oil to make the distillation

of Seneca oil into lamp oil profitable. He tries everything he can think

of. The Native Americans had historically collected the oil by damming

the creek near a seep and skimming the oil off the top. But Drake can

only collect six to ten gallons of oil a day this way, even when he

opens up extra seeps. He tries digging a shaft, but the groundwater

floods in too quickly.

By the summer of 1859 he’s

desperate. Drake’s running out of ideas, Bissell and Townsend are

running out of patience and, most importantly, the company is running

out of funds. He turns to “Uncle” Billy Smith, a Pittsburgh blacksmith

who had experience drilling brine wells with steam-powered equipment.

They get to work drilling down through the shale bedrock to reach the

oil. It’s maddeningly slow work, with the crude equipment struggling to

get through three feet of bedrock a day. By August 27th they’ve drilled

down 69 and a half feet, Drake has used the last of his funds, and

Bissell and his partners have decided to close up the operation. On

August 28th, they strike oil.

Narrator: Then on Sunday, August 28th, 1859, oil

bubbled up the drive pipe. Uncle Billy and his son Sam bailed out

several buckets of oil. On Monday, the very day that Colonel Drake

received his final payment and an order to close down the operation,

they hitched the walking beam to a water pump and the oil began to flow.

The first oil was to sell for $40 a barrel. Years later a local

newspaper interviewed Uncle Billy about the day they struck oil:

“I commenced drilling and at 4:00 I struck the oil. I says to

Mr. Drake, ‘Look there! What do you think of this?’ He looked down the

pipe and said, ‘What’s that?’ And I said, ‘That is your fortune!’”

Drake’s well proved that by drilling for it, oil could be

found in abundance and produced cheaply. Overnight a whole new industry

was born. Before long in millions of homes, farms and factories around

the world, lamps would be lit with kerosene refined from West

Pennsylvania crude.

Daniel Yergin: When the word came out that Drake had struck

oil, the cry went up throughout the narrow valleys of Western

Pennsylvania: ‘The crazy Yankee has struck oil! The crazy Yankee has

struck oil!’ And it was the first great boom. It was like a gold rush.

SOURCE: The Prize (Part 1)

Overnight the quiet farming

backwoods of rural Pennsylvania was transformed into a bustling oil

region, with prospectors leasing up flats, towns springing up from

nowhere, and a forest of percussion rigs covering the land. The first

oil boom had arrived.

Already poised to make the most

of this boom was a young up-and-coming bookkeeper in Cleveland with a

head for numbers: John Davison Rockefeller. He had two ambitions in

life: to make $100,000 and to live to 100 years old. John D. set off to

make his fortune in the late 1850s, armed with a $1000 loan from his

father, “Devil” Bill.

David Rockefeller: Grandfather never finished

high school and went to Cleveland having borrowed $1000 from his father

to start a business — paid 9% interest on it incidentally. And he read

about the oil business just beginning and got interested, and came to

realize it was a very volatile business at the time.

SOURCE: The Prize Part 1

In 1863, seeing the oil boom and

sensing the profits to be made in the fledgling business, Rockefeller

formed a partnership with fellow businessman Maurice B. Clark and Samuel

Andrews, a chemist who had built an oil refinery but knew little about

the business of getting his product to market. In 1865 the shrewd John

D. bought out his partners for $72,500 and, with Andrews as partner,

launched Rockefeller & Andrews. By 1870, after five years of

strategic partnerships and mergers, Rockefeller had incorporated

Standard Oil.

The story of the rise of Standard Oil is an oft-told one.

Narrator: In a move that would transform the

American economy, Rockefeller set out to replace a world of independent

oilmen with a giant company controlled by him. In 1870, begging bankers

for more loans, he formed Standard Oil of Ohio. The next year, he

quietly put what he called “our plan” — his campaign to dominate the

volatile oil industry — into devastating effect. Rockefeller knew that

the refiner with the lowest transportation cost could bring rivals to

their knees. He entered into a secret alliance with the railroads called

the South Improvement Company. In exchange for large, regular

shipments, Rockefeller and his allies secured transport rates far lower

than those of their bewildered competitors.

Ida Tarbell, the daughter of an oil man, later remembered how

men like her father struggled to make sense of events: “An uneasy rumor

began running up and down the Oil Regions,” she wrote. “Freight rates

were going up. … Moreover … all members of the South Improvement Company

— a company unheard of until now — were exempt. … Nobody waited to find

out his neighbor’s opinion. On every lip there was but one word and

that was ‘conspiracy.’”

Ron Chernow, Biographer: By 1879, when Rockefeller is 40, he

controls 90 percent of the oil refining in the world. Within a few

years, he will control 90 percent of the marketing of oil and a third of

all of the oil wells. So this very young man controls what is not only a

national but an international monopoly in a commodity that is about to

become the most important strategic commodity in the world economy.

SOURCE: The Rockefellers

By the 1880s, the American oil industry was the Standard Oil Company. And Standard Oil was John D. Rockefeller.

But it wasn’t long until a

handful of similarly ambitious (and well-connected) families began to

emulate the Standard Oil success story in other parts of the globe.

One such competitor emerged from the Caucasus in the 1870s, where Imperial Russia had opened up

the vast Caspian Sea oil deposits to private development. Two families

quickly combined forces to take advantage of the opportunity: the

Nobels, led by Ludwig Nobel and including his dynamite-inventing

prize-creating brother Alfred, and the French branch of the infamous

Rothschild banking dynasty, led by Alphonse Rothschild.

In 1891, the Rothschilds contracted

with M. Samuel & Co., a Far East shipping company headquartered in

London and run by Marcus Samuel, to do what had never been done before:

ship their Nobel-supplied Caspian oil through the Suez Canal to East

Asian markets. The project was immense; it involved not only

sophisticated engineering to construct the first oil tankers to be

approved by the Suez Canal Company, but the strictest secrecy. If word

of the endeavour was to get back to Rockefeller through his

international intelligence network it would risk bringing the wrath of

Standard Oil, which could afford to cut rates and squeeze them out of

the market. In the end they succeeded, and the first bulk tanker, the Murex, sailed through the Suez Canal in 1892 en route to Thailand.

In 1897 “M. Samuel & Co.”

became The Shell Transport and Trading Company. Realizing that reliance

on the Rothschild/Nobel Caspian oil left the company vulnerable to

supply shocks, Shell began to look to the Far East for other sources of

oil. In Borneo they ran up against Royal Dutch Petroleum, established in

The Hague in 1890 with the support of King William III of the

Netherlands to develop oil deposits in the Dutch East Indies. The two

companies, fearing competition from Standard Oil, merged in 1903 into the Asiatic Petroleum Company, jointly owned with the French Rothschilds, and in 1907 become Royal Dutch Shell.

Another global competitor to the

Standard Oil throne emerged in Iran at the turn of the 20th century. In

1901 millionaire socialite William Knox D’arcy negotiated an incredible concession

with the king of Persia: exclusive rights to prospect for oil

throughout most of the country for 60 years. After 7 years of fruitless

search, D’Arcy and his Glasgow based partner, Burmah Oil, were ready to

abandon the country altogether. In early May of 1908 they sent a

telegram to their geologist telling him to dismiss his staff, dismantle

his equipment and come back home. He defied the order and weeks later

struck oil.

Burmah Oil promptly spun off the

Anglo-Persian Oil Company to oversee production of Persian oil. The

British government took 51% majority control of the company’s shares in

1914 at the behest of Winston Churchill, then First Lord of the Admiralty, and survives today as BP.

The Rothschilds and Nobels. The

Dutch royal family. The Rockefellers. These early titans of the oil

industry and their corporate shells pioneered a new model for amassing

and expanding fortunes hitherto unheard of. They were the scions of a

new oligarchy, one built around oil and its control, from wellhead to

pump.

But it was not just about money.

The monopolization of this, the key energy resource of the 20th century,

helped secure the oiligarchs not just wealth but power over the lives

of billions. Billions who came to depend on black gold for the provision

of just about every aspect of their daily lives.

In the late 19th century,

however, it was by no means certain that oil would become the key

resource of the 20th century. As cheap illumination from the

newly-commercialized light bulb began to destroy the market for lamp

oil, the oiligarchs were on the verge of losing the value from their

monopoly. But a series of “lucky strikes” was about to catapult their

fortunes even further.

The very next year after the

commercial introduction of the light bulb, another invention came along

to save the oil industry: German engineer Karl Benz patented a reliable,

two-stroke internal combustion engine. The engine ran on gasoline,

another petroleum byproduct, and became the basis for the Benz

Motorwagen that, in 1888, became the first commercially available

automobile in history. And with that stroke of luck, the business that

Rockefeller and the other oiligarchs had spent decades consolidating was

saved.

But more luck was needed to

ensure the market for this new engine. In the early days of the

automobile era it was by no means certain that gas-powered cars would

come to dominate the market. Working models of electric vehicles had

been around since the 1830s, and the first electric car was built in 1884. By 1897 there was a fleet of all-electric taxis shuttling passengers around London. The world land speed record was set by an electric car in 1898. By the dawn of the 20th century electric cars accounted for 28% of the automobiles

in the United States. The electrics had advantages over the internal

combustion engine: they required no gear shifting or hand cranking, and

had none of the vibration, smell, or noise associated with gasoline-powered cars.

Lady Luck intervened again on

January 10, 1901, when prospectors struck oil at Spindletop in East

Texas. The gusher blew 100,000 barrels a day and set off the next great

oil boom, providing cheap, plentiful oil to the American market and

driving down gas prices. It wasn’t long before the expensive, low range

electric engines were abandoned altogether and big, loud, gas-guzzling

engines came to dominate the road, all fueled by the black gold that

Standard Oil, Shell, Gulf, Texaco, Anglo-Persian and the other oil

majors of the time were drilling, refining and selling.

Perhaps John D.’s greatest stroke

of luck, however, was not supposed to be luck at all. Rockefeller had

come under increasing scrutiny by a public outraged by the unprecedented

wealth he had amassed through Standard Oil. Muckraking reporters like

Ida Tarbell began digging up the dirt on his rise to power through

railroad conspiracies, secret deals with competitors and other shady

practices. The press pictured him as a colossus with bribed politicians literally in the palm of his hand; Standard Oil was a menacing octopus

with its tentacles strangling the lifeblood of the nation. Hearings

began, investigations were launched, lawsuits were brought against him.

And then, finally, in 1911 the Supreme Court made a monumental decision.

Narrator: On May 15th, 1911, the Supreme Court of

the United States declared that Standard Oil was a monopoly in

restraint of trade and should be dissolved. Rockefeller heard of the

decision while golfing at Kykuit with a priest from the local Catholic church, Father J.P. Lennon.

Ron Chernow, Biographer: And Rockefeller reacted with amazing

aplomb. He turned to the Catholic priest and said, “Father Lennon, have

you some money?” And the priest was very startled by the question and

said, “No.” And then he said, “Why?” And Rockefeller replied, “Buy

Standard Oil.”

Narrator: As Rockefeller foresaw, the individual Standard Oil

companies were worth more than the single corporation. In the next few

years, their shares doubled and tripled in value. By the time the rain

of cash was over, Rockefeller had the greatest personal fortune in

history — nearly two percent of the American economy.

Ron Chernow, Biographer: And it was really losing the

antitrust case that converted John D. Rockefeller into history’s first

billionaire. So that Standard Oil was punished in the federal antitrust

case, but John D. Rockefeller, Sr. most assuredly was not.

SOURCE: The Rockefellers

To the amazement of the world,

Rockefeller’s punishment had in fact been his reward. Rather than being

taken down a peg, the splitting up of the Standard Oil monopoly had

launched him as the world’s only acknowledged billionaire at a time when

the average annual income in America was $520.

Rockefeller’s story was perfectly

mirrored by the story of Colonel Edwin Drake. Having struck oil in

Titusville and given rise to a billion dollar global industry, Drake had

not had the foresight to patent his drilling technique or even to buy

up the land around his own well. He ended up in poverty, relying on an

annuity from the state of Pennsylvania to scrape together a living and

dying in 1880.

For the oiligarchy, the lesson of

the rise and rise of Rockefeller was obvious: the more ruthlessly that

monopoly was pursued, the tighter that control was grasped, the greater

the lust for power and money, the greater the reward would be in the

end.

From now on, no invention would

derail the oil majors from their quest for total control. No competition

would be tolerated. No threat to the oiligarchs would be allowed to

rise.

PART TWO: COMPETITION IS A SIN

John D. Rockefeller

When asked how he could justify

the treachery and deceit with which he pursued the creation of the

Standard Oil monopoly, John D. Rockefeller is reputed to have said:

“Competition is a sin.” This is the mentality of the monopolist, and it

is this justification, framed as religious conviction, that drove the

oiligarchs to so ruthlessly eliminate anyone who would dare rise up as a

pretender to their throne.

Ironically, it was the

competition between the oiligarchs in the early 20th century that helped

give rise to an early external threat to their empire: alcohol fuel.

As historian Lyle Cummins has noted

of the period: “The oil trust battles between Rockefeller, the

Rothschilds, the Nobels and Marcus Samuel’s Shell kept prices in a state

of flux, and engines often had to be adaptable to the fuel that was

available.”

In many areas where oil wasn’t

available, the alternative was alcohol. Ethyl alcohol had been used as a

fuel for lamps and engines since the early 19th century. Although it

was generally more expensive, alcohol fuel offered a stability of supply

that was alluring, especially in areas like London or Paris that did

not have predictable access to oil supplies.

Alcohol has a lower heat value, or BTU, than gasoline, but a series of tests

by the US Geological Survey and the US Navy in 1907 and 1908 proved

that the higher compression ratio of alcohol engines could perfectly

offset the lower heat value, thus making alcohol and gasoline engines

fuel economy equivalent.

One early supporter of alcohol fuel was Henry Ford, who designed his Model T

to run on either alcohol or gasoline. Sensing an opportunity for new

markets to boost the independent American farms that he felt were vital

to the nation, Henry Ford told the New York Times:

“The fuel of the future is going

to come from fruit like that sumach out by the road, or from apples,

weeds, sawdust – almost anything. There is fuel in every bit of

vegetable matter that can be fermented.”

Farmers, looking to capitalize on

this, lobbied for the repeal of a $2.08 per gallon alcohol tax that had

been imposed to help pay for the Civil War. They were aided by those

who saw fuel alcohol as a way to break the oiligarchs’ monopoly. In

support of a bill to repeal the alcohol tax, President Teddy Roosevelt told the US Congress in 1906:

“The Standard Oil Company has,

largely by unfair or unlawful methods, crushed out home competition. It

is highly desirable that an element of competition should be introduced

by the passage of some such law as that which has already passed the

House, putting alcohol used in the arts and manufactures upon the free

list.”

The alcohol tax was repealed in

1906 and for a time corn ethanol at 14 cents a gallon was cheaper than

gasoline at 22 cents a gallon. The promise of cheap, unpatentable,

unmonopolizable fuel production, production open to anyone with raw

vegetable matter and a still, swept the nation.

But cheap, plentiful fuel that can be grown and produced locally and independently is not what the oiligarchs had in mind.

A 1909 USGS report

comparing gas and alcohol engines had noted that a significant point in

alcohol fuel’s favour was that there were fewer restrictions on alcohol

engines. For the oiligarchs, the answer was simple: find a way to place

greater restrictions on alcohol engines. Thankfully for them, the

answer to their problem was already gaining popular support.

In the 19th century, America had a drinking problem. By 1830, the average American over 15 years old drank seven gallons of pure alcohol per year,

three times higher than today’s average. This led to the first

anti-alcohol movements in the 1830s and 1840s, and the formation of the

Prohibition Party in 1869 and the Women’s Christian Temperance Union in

the 1870s. The movement enjoyed widespread and growing support but had

few political successes; Maine flirted with prohibition by outlawing the sale and manufacture of liquor in 1851, but the ban only lasted five years.

This changed with the formation

of the Anti-Saloon League in Standard Oil’s birth state of Ohio in 1893.

The ASL was started by John D. Rockefeller’s long-time personal friend Howard Hyde Russell and was bankrolled in part by generous annual donations

from Rockefeller himself. The ASL, with Rockefeller’s backing, quickly

became the driving force behind a national movement to outlaw the

production and sale of alcohol.

Rockefeller was a teetotaler himself, not from moral concern but because he was afraid that “good cheer among friends”

would lead to his downfall in business. Stephen Harkness, one of the

silent partner investors in Standard Oil and a director in the company

until his death, had caught Rockefeller’s eye

when he made a fortune buying up whiskey in advance of a new excise tax

that he had been tipped about and selling it at a huge profit after the

tax kicked in.

No, Rockefeller and Standard Oil

were not concerned about the moral state of the nation…except as far as

it impacted their bottom line. But when prohibition did come in 1920, it

had an interesting side effect: although it didn’t ban the use of

ethanol as a fuel directly, it did lead to increasingly burdensome restrictions

requiring producers to add petroleum products to their ethanol to make

it poisonous before it could be sold. Alcohol fuel, now completely

unable to compete with gasoline, was abandoned altogether by the

automobile industry.

Another existential threat to the

vast fortunes of the early oiligarchs was to require an even greater

effort at social engineering: public transportation.

By the end of World War I,

private car ownership was still a relative rarity; only one in 10

Americans owned a car. Rail was still the transportation of choice for

the vast majority of the public, and city-dwellers in most major cities

relied on electric trolley networks to transport them around town. In

1936, General Motors formed a front company, “National City Lines,”

along with Firestone Tire and Standard Oil of California, to implement a

process of “bustitution”: scrapping streetcars and tearing up railways

to replace them with GM’s own buses running on Standard Oil supplied

diesel. The plan was remarkably successful.

As historian and researcher F. William Engdahl notes in “Myths, Lies and Oil Wars”

“By the end of the 1940s, GM had

bought and scrapped over one hundred municipal electric transit systems

in 45 cities and put gas-burning GM buses on the streets in their place.

By 1955 almost 90% of the electric streetcar lines in the United States

had been ripped out or otherwise eliminated.”

The cartel had been careful to

hide their involvement in National City Lines, but it was revealed to

the public in 1946 by an enterprising retired naval lieutenant

commander, Edwin J. Quinby. He wrote a manifesto

exposing what he called “a careful, deliberately planned campaign to

swindle you out of your most important and valuable public

utilities–your Electric Railway System.” He uncovered the oiligarchs’

stock ownership of National City Lines and its subsidiaries and detailed

how they had step by step bought up and destroyed the public

transportation lines in Baltimore, Los Angeles, St. Louis and other major urban centres.

Quinby’s warning caught the attention of federal prosecutors and in 1947 National City Lines was indicted

for conspiring to form a transportation monopoly and conspiring to

monopolize sales of buses and supplies. In 1949, GM, Firestone, Standard

Oil of California and their officers and corporate associates were

convicted on the second count of conspiracy. The punishment for buying

up and dismantling America’s public transportation infrastructure? A

$5,000 fine. H. C. Grossman, who had been the director of Pacific City

Lines when it oversaw the scrapping of LA’s $100 million Pacific

Electric system, was fined exactly $1.

Unsurprisingly, GM and its

associates did not remain in the doghouse for long. In 1953 President

Eisenhower appointed Charles Wilson, then the President of General

Motors, as Secretary of Defense. Wilson, with Francis DuPont of the

Rockefeller-connected DuPont family as Chief Administrator of Federal

Highways, oversaw one of the largest public works projects in American

history: the creation of the interstate highway system. With a war-era

excise tax on train tickets still in place and federally funded highways

and airports providing cheaper alternatives, rail travel declined a startling 84% between 1945 and 1964.

This social engineering paid off

well for Standard Oil and its growing list of petrochemical associates.

In the two and a half decades after the outbreak of World War II,

vehicle production in Detroit almost tripled, from 4.5 million cars a

year in 1940 to over 11 million in 1965. As a result, sales of refined

gasoline over the same period rose 300%.

But Rockefeller was not the only

oiligarch working to crush all opposition to his monopoly. Across the

pond, the European oiligarchs were working to protect their own oil

investments from upstart competitors.

In 1889, a consortium of German

investors led by Siemens’ Deutsche Bank obtained a concession from the

Turkish government for extension of a railway line connecting Berlin to

Basra on the Persian Gulf via Baghdad in what was then part of the

Ottoman Empire. The Berlin-Baghdad Railway

concession was for ninety-nine years and came with mineral rights for

twenty kilometers on either side of the line…an especially lucrative

deal since the rail cut right through the heart of the still untapped

Mesopotamian oil regions south of Mosul along the Tigris River.

For the powers behind the British empire, concerned with the military rise of Germany, this deal was unacceptable.

William Engdahl: Well Germany in the end of the

19th century was looking for outlets for its exports — its industrial

exports — as the German economy was growing like China’s has grown in

the last 30 years. And they decided that Turkey would be an ideal

strategic trade partner for Germany. And Georg von Siemens, one of the

directors of Deutsche Bank, came up with a strategy to extend a railway

from Berlin all the way down to Baghdad — which was then part of the

Ottoman Empire, Baghdad and Iraq today, near the Persian Gulf. German

military began training the Turkish military. German industry began

investing in Turkey. They saw a huge potential market to begin bringing

Turkey into the 20th century economically. Deutsche Bank also negotiated

mineral rights — I think it was 20 kilometres either side of the

railway — and it was already known in 1914 that Mosul and these other

areas contained huge petroleum deposits.

Well, why is that significant? At the end of the 19th

century, Jack Fisher–the head of the Admiralty and the head of the Royal

Navy–advocated the conversion of the British Navy from coal-fired to

oil-fired. That it would have a qualitative strategic improvement in

every aspect of warship design. And since Britain didn’t know that they

had any oil back then they went to Persia and swindled the Shah out of

oil rights in Persia. They went to Kuwait and backed a coup d’etat of

the Al-Sabah family to be a British pawn, and they literally wrote a

contract with him that nothing that Kuwait does will be done without

approval of the British Governor. And Kuwait was known to have oil lying

right on the Persian Gulf.

The British looked at this railway plan of the Germans going

right down to Baghdad and said ‘My God! You can put soldiers on rail

cars and bring them down and threaten the oil lifeline of the British

Navy.’ This is a strategic move by the Germans. It also would make

Germany independent of the British control of the seas. They would have a

landline much like the Chinese “One Belt, One Road” infrastructure for

high speed rails going throughout Eurasia into Russia, on into Belarus

and Western Europe that removes the United States’ Navy ability to

control China and control Central Asia to a great extent.

The British oiligarchs, including the British crown with its hidden controlling stake in Anglo-Persian Oil and the Rothschild’s merchant Marcus Samuel

at Royal Dutch Shell, sought to counter this German threat to their

commercial and strategic interests. They used Armenian-born naturalized

British citizen Calouste Gulbenkian–the architect of the Royal Dutch /

Shell merger–in order, as he later recalled “to see British influence get the upper hand in Turkey” against the Germans. If that was his task, it was a remarkable success.

In 1909 the British set up the

Turkish National Bank, which was “Turkish” in name only. Founded by

London banker Sir Edward Cassel and with directors like Hugo Baring of

the Barings banking family, Cassel himself, and Gulbenkian, the Bank set

up the Turkish Petroleum Company in 1912. Formed explicitly to exploit

the petroleum-rich oil fields of Iraq, then part of the Ottoman Empire,

Gulbenkian brokered a deal that forced Deutsche Bank, with its 40

kilometre concessions along the oil-rich Baghdad railway line, into a

junior partnership in the company. The stock was split so the British

government’s Anglo-Persian Oil Company owned half the shares, with Royal

Dutch Shell and Deutsche Bank splitting the other half.

Their plan to take over Germany’s

Turkish oil interests had been successful, but in an amazing irony, it

didn’t even matter. Gulbenkian finished negotiations for the Iraqi oil

concession on June 28, 1914,

the same day Archduke Ferdinand was shot in Sarajevo. An alliance the

British had been brokering for years to constrain the rising German

threat, an alliance involving France and Russia, kicked into motion and

the world was engulfed in war. By the end of World War I, the British

and their allies had taken over Iraq and its oil deposits anyway,

Germany had been completely cut out, and Gulbenkian, their scheming

servant, received 5% of all oil field proceeds in the newly minted

country.

As the century wore on, the oil

industry grew beyond the control of the handful of families that had

dominated it since its inception. Oil deposits were located around the

globe and the resources of entire nation states were marshaled to

control them. Now, threats to the oiligarchs and their interests

required multi-lateral, multi-national responses and the consequences of

those deals were felt worldwide.

The story of the Oil Shock of 1973 as it has been delivered to us by the history books is well known.

Narrator: By the late 1960s the nation relied on

imported oil to keep the economy strong. Then in the early 1970s

oil-dependent America’s nightmares came true: 13 oil-producing countries

in the Middle East and South America formed OPEC, the Organization of

Petroleum Exporting Countries. In 1973 OPEC placed an oil embargo on the

US and other nations that had supported Israel against the Arab states

in the Yom Kippur war. The American economy went into a tailspin as gas

shortages gripped the nation.

SOURCE: History of Oil

Few, however, know that the

crisis and its ensuing response was in fact prepared months ahead of

time at a secret meeting in Sweden in 1973. The meeting was the annual

gathering of the Bilderberg Group, a secretive cabal formed by Prince

Bernhard of the Netherlands in 1954.

The Dutch royal family not only gave its royal imprint to Royal Dutch Petroleum, they are still rumoured to be, along with the Rothschilds,

one of the largest shareholders in Royal Dutch Shell, from the days

when Queen Wilhelmina’s Anglo-Dutch Petroleum holdings and other

investments made her the world’s first female billionaire

right through to today. Bernhard’s guest list at the Bilderberg Group

reflected his position in the oiligarchy; alongside him at the Swedish

conference were David Rockefeller of the Standard Oil dynasty and his

protege Henry Kissinger, Baron Edmond de Rothschild, E.G. Collado, the

Vice President of Exxon, Sir Denis Greenhill, director of British

Petroleum, and Gerrit A. Wagner, president of Bernhard’s own Royal Dutch

Shell.

At the meeting in Sweden, held

five months before the oil crisis began, the oil-igarchs and their

political and business allies were planning their response to a monetary

crisis that threatened the world dominance of the US dollar. Under the

Bretton Woods system, negotiated in the final days of World War II, the

US dollar would be the backbone of the world monetary system,

convertible to gold at $35 per ounce with all other currencies pegged to

it. Increasing US expenditures in Vietnam and decreasing exports caused

Germany, France, and other nations to start demanding gold for their

dollars.

With the Federal Reserve’s

official gold holdings plunging and unable to stem the tide of demand,

Nixon abandoned Bretton Woods in August 1971, threatening the dollar’s

position as the world reserve currency.

Richard Nixon: Accordingly, I have directed the

Secretary of the Treasury to take the action necessary to defend the

dollar against the speculators. I have directed Secretary Connally

to suspend temporarily the convertability of the dollar into gold or

other reserve assets except in amounts and conditions determined to be

in the interest of monetary stability and in the best interest of the

United States.

SOURCE: Nixon Ends Bretton Woods

As leaked documents from the 1973

Bilderberg meeting show, the oiligarchs decided to use their control

over the flow of oil to save the American hegemon. Acknowleding

that OPEC “could completely disorganize and undermine the world

monetary system,” the Bilderberg attendees prepared for “an energy

crisis or an increase in energy costs,” which, they predicted, could mean an oil price between $10 and $12, a staggering 400% increase from the current price of $3.01 per barrel.

Five months later, Bilderberg attendee and Rockefeller protege Henry Kissinger, acting as Nixon’s Secretary of State, engineered the Yom Kippur War

and provoked OPEC’s response: an oil embargo of the US and other

nations that had supported Israel. On October 16, 1973, OPEC raised oil

prices by 70%. At their December meeting, the Shah of Iran demanded and

received a further price raise to $11.65 a barrel, or 400% of oil’s

pre-crisis price. When asked by Saudi King Faisal’s personal emissary

why he had demanded such a bold price increase, he replied: “Tell your King, if he wants the answer to this question, he should go to Washington and ask Henry Kissinger.”

In the second move of the

operation, Kissinger helped negotiate a deal with Saudi Arabia: in

exchange for US arms and military protection, the Saudis would price all

their future oil sales in dollars and recycle those dollars through

treasury purchases via Wall Street banks. The deal was a bonanza for the

oiligarchs; not only did they get to pass the price increases on to the

consumers, but they benefited from the huge flows of money into their

own banks. The Shah of Iran parked the National Iranian Oil Company’s

revenues in Rockefeller’s own Chase Bank, revenues that reached $14

billion per year in the wake of the oil crisis.

With the creation of this new system, the “petrodollar“,

the oiligarchs had reached unprecedented levels of control over the

economy. Not only that, they had backed the world monetary system with

their commodity, oil, and brought potential competition from upstart

producer nations under their control all in one step.

But for the insatiable appetites of these monopolist titans, mere control over the world’s monetary system was not enough…

PART THREE: THE WORLD IN THEIR IMAGE

In the nineteenth century,

railroad conspiracies and predatory pricing had been enough to assure

the oiligarchs’ monopoly. But by the time that the British crown, the

Dutch royal family, the Rothschilds and the other European oiligarchs

began opening up the Middle East and the Far East to oil exploration in

the early twentieth century, the goal was no longer to maximize profits

or control the oil industry. It was not even to control international

diplomacy. It was to control and shape the world itself. Its resources.

Its environment. And its people.

In order to achieve this goal, the oiligarchy would need a facelift.

In the current age, with the

Rockefeller name now more likely to be associated with Rockefeller Plaza

or Rockefeller University than Standard Oil, it is difficult to

understand just how hated John D. was in his own day. He was the head of the Standard Oil Hydra, an octopus strangling the world in his tentacles, a cutthroat gardener

pruning the competitors from the flower of his oil monopoly. As one of

the richest men the world had ever known, he was an easy target for the

average working man’s frustrations and a magnet for the poor seeking

help.

Judith Sealander, Historian: He received on

average 50 to 60,000 letters a month, asking for help. Dozens of people

followed him in the street. Literally, crowds stood around the Standard

Oil offices waiting for him to come out. Little children, painfully

thin, crying in the street and so on. Rockefeller felt overwhelmed.

SOURCE: The Rockefellers

Besieged by the downtrodden,

despised by the working man, hounded by Ida Tarbell and the muckraking

press, John D. had the mother of all PR problems. The answer was simple:

invent the PR industry. He hired Ivy Ledbetter Lee, a

journalist-turned-communications expert who invented the modern public

relations industry to burnish the Rockefellers’ tarnished image. It was

Lee that suggested giving the family name to Rockefeller Center and

filming John D. handing out dimes in public.

Narrator: An early master of public relations,

Lee used the media which the muckrakers had used to disgrace Rockefeller

to turn him into a sympathetic figure. Ivy Lee recognized early the

power of the new moving picture and used newsreels to show a remarkably

benevolent Rockefeller.

John D. Rockefeller: I am very grateful to you and to a host of people who are so kind and good to me all the time.

Second Man: Why, because you’re so good to everybody.

John D. Rockefeller: Yes, you are.

As Ivy Lee began to control his public image he became oddly a

kind of American character, and people kind of warmed to him in a

bizarre sort of way. It was like having Frankenstein on the loose

walking around New York City or something like that, with a cane and a

long hat.

Narrator: Although this plane never takes off, this photo

opportunity was presented as Senior’s first flight. Perhaps Ivy Lee’s

most brilliant public relations move was the casting of Rockefeller as

‘The Man Who Gave out Dimes.’

Man off camera: Don’t you give dimes, Mr. Rockefeller? Please, go ahead.

Woman: Thank you, sir.

Man: Thank you very much.

John D. Rockefeller: Thank you for the ride!

Man: I consider myself more than amply paid.

John D. Rockefeller: Bless you! Bless you! Bless you!

SOURCE: John D. Rockefeller – Standard Oil

These PR stunts seem obvious and

ham-handed by today’s standards, but they were effective enough: to this

day people leave dimes on the stone marker at the base of the 70 foot

Egyptian obelisk that towers over John D.’s final resting place in

Cleveland’s Lake View Cemetery. But it was not stage-managed photo

opportunities like these that transformed Rockefeller into a public

hero.

In order to win the public over,

he was going to have to give them what they wanted. And what they wanted

wasn’t difficult to understand: money. But just as his father, Devil

Bill, had taught him to do in all his business dealings, Rockefeller

made sure to get the better end of the bargain. He would “donate” his

great wealth to the creation of public institutions, but those

institutions would be used to bend society to his will.

As every would-be ruler

throughout history has realized, society has to be transformed from the

ground up. Americans in the 19th century still prized education and

intellectual pursuits, with the 1840 census finding unsurprisingly that

the United States–a nation that had been mobilized by tracts like Thomas

Paine’s remarkably popular Common Sense–was a nation of

readers, with a remarkable 93% to 100% literacy rate. Before the first

compulsory schooling laws in Massachusetts in 1852, education was

private and decentralized, and as a result classical education,

including study of Greek and Latin and a solid grounding in history and

science, was widespread.

But a nation of individuals who

could think for themselves was anathema to the monopolists. The

oiligarchs needed a mass of obedient workers, an entire class of people

whose intellect was developed just enough to prepare them for lives of

drudgery in a factory. Into the midst stepped John D. Rockefeller with

his first great act of public charity: the establishment of the

University of Chicago.

He was aided in this task by

Frederick Taylor Gates, a Baptist minister that Rockefeller befriended

in 1889 and who would go on to be John D.’s most trusted philanthropic

adviser. Gates would go on to write a short tract, “The Country School of Tomorrow,” that laid out the Rockefeller plan for education:

“In

our dream, we have limitless resources, and the people yield themselves

with perfect docility to our molding hand. The present educational

conventions fade from our minds; and, unhampered by tradition, we work

our own good will upon a grateful and responsive folk. We shall not try

to make these people or any of their children into philosophers or men

of learning or science. We are not to raise up from among them authors,

orators, poets, or men of letters. We shall not search for embryo great

artists, painters, musicians. Nor will we cherish even the humbler

ambition to raise up from among them lawyers, doctors, preachers,

politicians, statesmen, of whom we now have ample supply.”

Although Rockefeller’s resources

weren’t exactly limitless, they might as well have been. In 1902 he

established the General Education Board to help implement Gates’ vision

for the country school of tomorrow with a staggering $180 million

endowment.

The Rockefeller influence on

education was felt almost immediately, and it was amplified by help from

fellow monopolists of the era who were approaching the topic of

philanthropy from the same angle.

Although best known as a steel

magnate, Andrew Carnegie’s fortune started on the railroads transporting

Rockefeller’s Standard Oil around the country, and was greatly

magnified by a lucrative investment in property near Oil Creek that

provided steady, profitable oil sales. In 1905 he established the

Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, a tax-free

foundation through which Carnegie and his appointees could direct the

development of the education system in the the United States, and,

eventually, worldwide. In 1910, Rockefeller followed suit by

establishing the Rockefeller Foundation, which became the tax-free

umbrella organization for his philanthropic ambitions.

As the Reece Committee–a

Congressional investigation into the activities of these tax-free

foundations in the 1950s–discovered, it wasn’t long before Carnegie’s

Endowment approached Rockefeller’s Foundation with a proposal: to

cooperate on their shared desire to transform the American education

system in their own image. Norman Dodd, the director of research for the

Congressional committee who was granted access to the Carnegie

Endowment’s board minutes, explains:

So they approach the Rockefeller Foundation with a

suggestion: that portion of education which could be considered

domestic should be handled by the Rockefeller Foundation, and that

portion which is international should be handled by the Endowment.

They then decide that the key to the success of these two

operations lay in the alteration of the teaching of American History.

So, they approach four of the then most prominent teachers of American

History in the country — people like Charles and Mary Byrd. Their

suggestion to them is this, “Will they alter the manner in which they

present their subject”” And, they get turned down, flatly.

So, they then decide that it is necessary for them to do as they say, i.e.

“build our own stable of historians.” Then, they approach the

Guggenheim Foundation, which specializes in fellowships, and say” “When

we find young men in the process of studying for doctorates in the field

of American History, and we feel that they are the right caliber, will

you grant them fellowships on our say so? And the answer is, “Yes.”

So, under that condition, eventually they assemble twenty

(20), and they take these twenty potential teachers of American History

to London. There, they are briefed in what is expected of them — when, as, and if they secure appointments in keeping with the doctorates they will have earned.

That group of twenty historians ultimately becomes the

nucleus of the American Historical Association. And then, toward the end

of the 1920’s, the Endowment grants to the American Historical

Association four hundred thousand dollars ($400,000) for a study of our

history in a manner which points to what this country look forward to,

in the future.

That culminates in a seven-volume study, the last volume of

which is, of course, in essence, a summary of the contents of the other

six. The essence of the last volume is this: the future of this country

belongs to collectivism, administered with characteristic American

efficiency.

SOURCE: Norman Dodd interview

With this base for transformation

firmly established, the Rockefeller Foundation and like-minded

organization embarked on a program so ambitious that it almost defies

comprehension.

They transformed the practice of medicine.

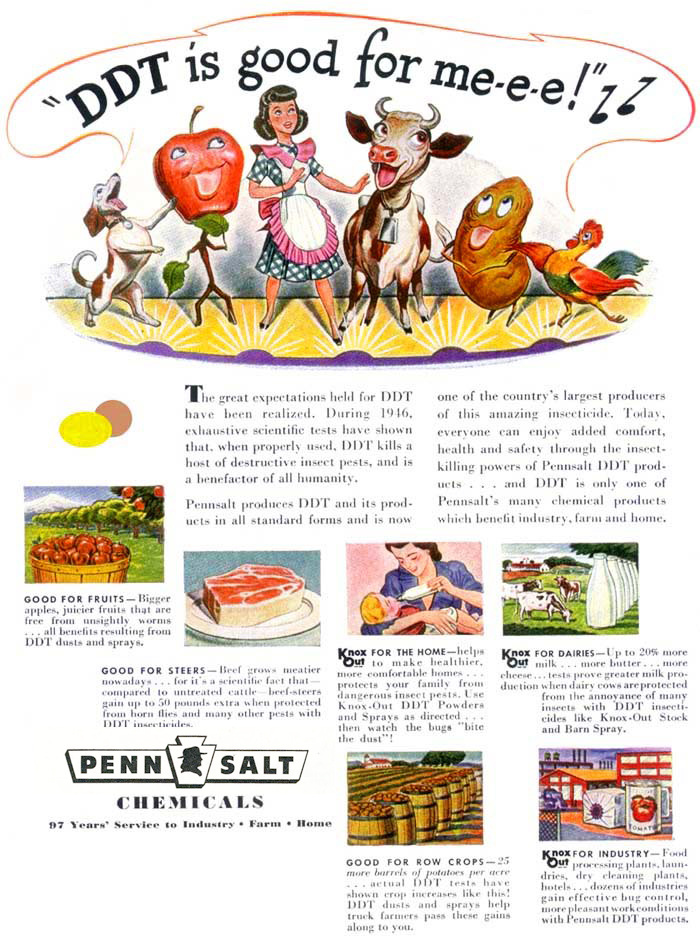

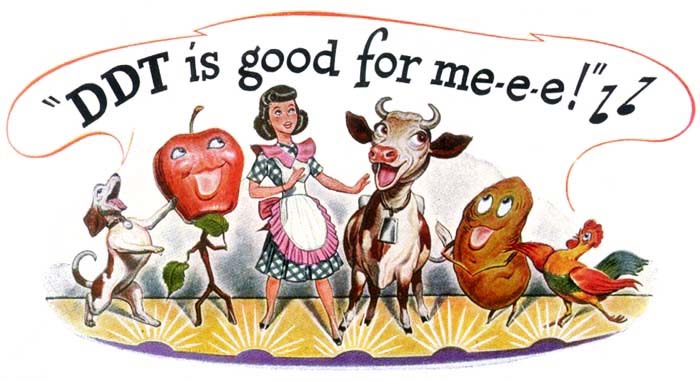

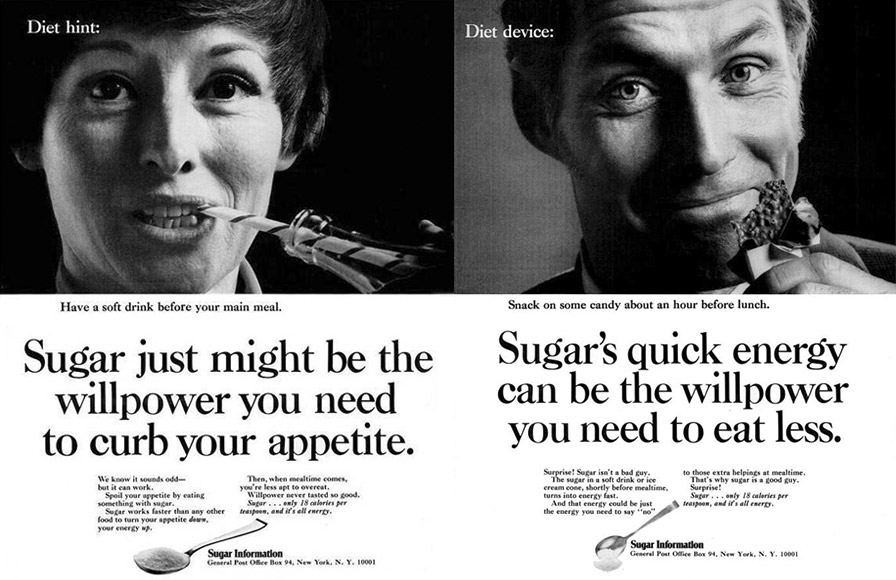

As usual, the oiligarchs that

funded this change were also there to profit from it, and once again

John D. took his queue from “Devil” Bill’s example. William Rockefeller

had called his brand of snake oil “Nujol,” for “new oil,” and Standard

Oil spun off “Nujol”

as a laxative under their Stanco subsidiary. Manufactured on the same

premises as “Flit,” an insecticide also derived from Standard Oil’s

byproducts, “Nujol” sold at the druggist for 28 cents per six ounce

bottle; it cost Standard Oil less than one-fifth of a cent to

manufacture. Pharmaceuticals provided a lucrative new opportunity for

the oiligarchs, but in a turn-of-the-century America that was still

largely based on naturopathic, herbal remedies, it was a tough sell. The

oiligarchy went to work changing that.

In 1901 John D. established the

Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research. The Institute recruited

Simon Flexner, a pathology professor at the University of Pennsylvania,

to serve as its director. His brother, Abraham, was an educator who was

contracted by the Carnegie Foundation to write a report on the state of

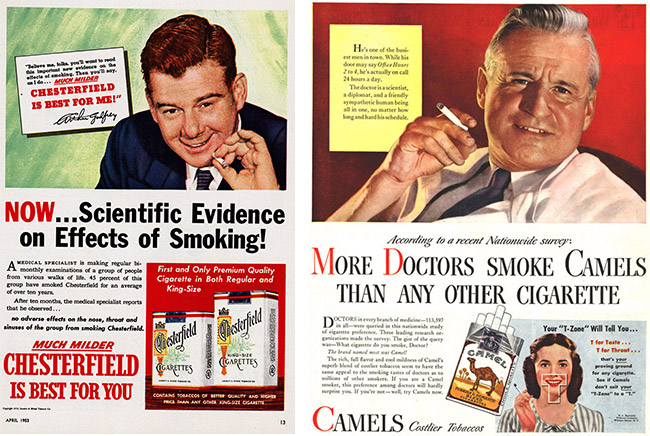

the American medical education system. His study, The Flexner Report, along with the hundreds of millions of dollars

that the Rockefeller and Carnegie Foundations were to shower on medical

research in the coming years, resulted in a sweeping overhaul of the

American medical system. Naturopathic and homeopathic medicine, medical

care focused on un-patentable, uncontrollable natural remedies and cures

was now dismissed as quackery; only drug-based allopathic medicine

requiring expensive medical procedures and lengthy hospital stays was to

be taken seriously.

Narrator: The fortunes of Carnegie, Morgan and

Rockefeller financed surgery, radiation and synthetic drugs. They were

to become the economic foundations of the new medical economy.

G. Edward Griffin: The takeover of the medical industry was

accomplished by the takeover of the medical schools. Well, the people

that we’re talking about, Rockefeller and Carnegie in particular, came

to the picture and said ‘We will put up money.’ They offered tremendous

amounts of money to the schools that would agree to cooperate with them.

The donors said to the schools: ‘We’re giving you all this money, now

would it be too much to ask if we could put some of our people on your

Board of Directors to see that our money is being spent wisely?’ Almost

overnight all of the major universities received large grants from these

sources and also accepted one, two or three of these people that I

mentioned on their Board of Directors and the schools literally were

taken over by the financial interests that put up the money.

Now what happened as a result of that is the schools did

receive an infusion of money, they were able to build new buildings,

they were able to add expensive equipment to their laboratories, they

were able to hire top-notch teachers, but at the same time as doing that

they schewed the whole thing in the direction of pharmaceutical drugs.

That was the efficiency in philanthropy.

The doctors from that point forward in history would be

taught pharmaceutical drugs. All of the great teaching institutions in

America were captured by the pharmaceutical interests in this fashion,

and it’s amazing how little money it really took to do it.

SOURCE: The Money Takeover Of Medicine

The oiligarchy birthed entire medical industries

from their own research centers and then sold their own products from

their own petrochemical companies as the “cure.” It was Frank Howard, a

Standard Oil of New Jersey executive, who would go on to persuade Alfred

Sloan and Charles Kettering to donate their fortunes to the cancer

center that would then bear their name. As director of research at Sloan-Kettering, Howard appointed Cornelius Rhoads,

a Rockefeller Institute pathologist, to develop his wartime research on

mustard gas for the US Army into a new cancer therapy. Under Rhoads’

leadership, nearly the entire program and staff of the Chemical Warfare

Service were reformed into the SKI drug development program, where they

worked on converting mustard gas into chemotherapy. And once again, the Rockefeller’s own snake oil was being sold as a cancer cure-all.

The oiligarchs’ interest in the

burgeoning pharmaceutical industry converged in companies like I.G.

Farben, a drug and chemical cartel formed in Germany in the early 20th

century. Royal Dutch’s Prince Bernhard served on an I.G. Farben subsidiary’s board in the 1930s and the cartel’s American operation, set up in cooperation with Standard Oil, included on its board

Standard Oil president Walter Teagle as well as Paul Warburg of Kuhn,

Loeb & Co., itself headed by Jacob Schiff of the Rothschild broker

family. At its height, I.G. Farben was the largest chemical company in

the world and the fourth largest industrial concern in the world, right

behind Standard Oil of New Jersey.

The company was broken up after

World War II, but like Standard Oil, its various pieces remained intact

and today BASF, one of its chemical offshoots, remains the largest chemical company in the world, while Bayer and Sanofi, two of its pharmaceutical offshoots are among the largest pharmaceutical companies in the world.

Not content merely to monopolize

the fields of education and medicine, the same oiligarchical interests

banded together to take control of America’s finances. In 1910 John D.

Rockefeller Jr.’s own father-in-law, Senator Nelson Aldrich, Frank

Vanderlip of the National City Bank, and Paul Warburg, as well as

various agents of J.P. Morgan, met in complete secrecy on Jekyll Island

to hammer out the details of what would go on to become the Federal

Reserve, America’s central bank. The Fed, established in 1913, would be

run by hand-picked appointees of the oiligarchy and their banking

associates, including, perhaps inevitably, Standard Oil president and

American I.G. director Walter Teagle.

The Rockefeller family would go

on to formally enter the banking field in the 1950s when James Stillman

Rockefeller, the grandson of John D.’s brother, was appointed director

of National City Bank. Meanwhile John D.’s own grandson, David

Rockefeller, would go on to take over Chase Manhattan Bank, the

long-time banking partner of the Standard Oil empire.

In this move the Rockefellers’

story perfectly mirrored that of their fellow oiligarchs the

Rothschilds. Whereas the Rothschilds had supplemented their banking

fortune with their oil interests, the Rockefellers supplemented their

oil fortune with banking interests.

Springboarding from success to

success as they consolidated monopolies across every field of human

activity, the oiligarchs’ ambitions became even larger. This time, their

goal was to consolidate control over the very food supply of the world

itself, and once again they would use philanthropy as the cover for

their business takeover.

Narrator: The Green Revolution began in 1943 when

plant geneticist Norman Borlaug and a team of researchers arrived on

Mexican soil. His goal was to improve agricultural techniques and

biotechnological methodologies which in turn would help alleviate

starvation and improve the living quality of developing nations.

Creating new genetically modified strains of wheat, rich, maize and

other crops, Borlaug planned to win the battle against world hunger. The

hope was that these new crops and farming techniques would rescue third

world countries from the brink of starvation.

That’s exactly what happened. The agricultural innovations

brought to the poverty-stricken countries gave the farmers the skills

and resources necessary to sustain themselves. This triggered a chain of

events that would allow these once-struggling nations to survive.

Agricultural exports soared in quantity and diversity and allowed the

countries to become self-sufficient.

As the genetically modified crops thrived, farmers were able

to use their increased income to purchase newer and superior farming

machinery. This increase in revenue made farming easier, more reliable

and more efficient. The Green Revolution led to the modernization of

agriculture and has had a profound social, economic and political impact

on the world.

The Mexican government turned to the Rockefeller Foundation in their endeavour to nourish Mexico through agriculture.

SOURCE: Green Revolution Waging War Against Hunger

Norman Borlaug, needless to say,

was a researcher for the Rockefeller Foundation, and the Green

Revolution, for whatever increase in yields it brought about, also

created markets for the oiligarchs’ own interest in the petrochemical

fertilizer industry and gave rise to the “ABCD” seed cartel

of Archer Daniels Midand, Bunge, Cargill and Louis Dreyfus. These

companies, along with their associated interests in the food packaging

and processing industry, formed the core of American “agribusiness,” a

concept developed at Harvard Business School in the 1950s with the help of research conducted by Wassily Leontief for the Rockefeller Foundation.

The American agribusiness giants

shared a common goal: the transformation of third world agriculture into

a captive market for their goods. From this perspective, the project

was a runaway success. By the 1970s the Rockefeller Standard Oil network

and its cronies in the nitrogen fertilizer industry (including DuPont,

Dow Chemical, and Hercules Powder) had broken into markets around the

world, markets conveniently forced open for them by the US government

itself under President Johnson’s “Food for Peace”

program, which mandated the use of petrochemical-dependent agricultural

technologies (fertilizers, tractors, irrigation, etc.) by aid

recipients.

Unable to afford these new

technologies themselves, the impoverished third-world “beneficiaries” of

this “revolution” relied on loans from the International Monetary Fund

and the World Bank handled by Rockefeller’s own Chase Manhattan Bank and

guaranteed by the US government.

The real costs of the Green

Revolution, economic, agricultural and environmental are seldom tallied.

Access to these debt-financed petrochemical-dependent technologies

exacerbated the difference between the rich landowning class and the

landless peasants in countries like India, where land reform and abolition of usury were dropped from the political agenda after the Green Revolution took over.

Even then, the revolution’s main success, its increase in agricultural yields, has been oversold. Yield growth across India actually slowed after the introduction of agribusiness. The environmental destruction is even more devastating. An overview in the December 2000 edition of Current Science notes: “The green revolution has not only increased productivity, but it has also [produced] several negative ecological consequences such as depletion of lands, decline in soil fertility, soil salinisation, soil erosion, deterioration of environment, health hazards, poor sustainability of agricultural lands and degradation of biodiversity. Indiscriminate use of pesticides, irrigation and imbalanced fertilization has threatened sustainability.”

The Rockefeller Foundation even acknowledges

the critiques of the Green Revolution it funded into existence,

insisting that “current initiatives take into account lessons learned.”

Even so, the Foundation continues to fund research and write reports on how to improve prospects for agribusiness investment in its target markets.

As egregious as the Green

Revolution was and continues to be, however, in many ways it was just

the prelude to an even more ambitious project: the Gene Revolution. Now

the project is not merely to monopolize the technologies, supplies and

chemical inputs for agriculture worldwide, but to monopolize the food

supply itself through the replacement of the world’s natural seeds with

patentable genetically modified crops.

The players involved in this

“Gene Revolution” are almost identical to the players in the Green

Revolution, with I.G. Farben offshoots Bayer CropScience and BASF

PlantScience mingling with traditional oiligarch associate companies

like Dow AgroScience, DuPont Biotechnology, and, of course, Monsanto,

all funded by the Rockefeller Foundation and fellow “philanthropists” at

the Ford Foundation, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and

like-minded organizations.

The convergence of corporate,

“philanthropic,” governmental and inter-governmental interests in

promoting GM crops around the world can be seen in the bewildering array

of research institutes, industry associations, and “consultative

groups” devoted to the case. The Rockefeller-funded International Rice Research Institute (IRRI), the Rockefeller/Monsanto/USAID brainchild International Service for the Acquisition of Agri-biotech Applications (ISAAA), the Rockefeller/Ford/World Bank created

Consultative Group of International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) and

dozens of other bland, benign-sounding organizations research and

promote GM crops in target markets around the globe, with the profits

ending up in the oiligarchs’ coffers.

A representative example of this

story is the agribusiness neocolonization of Argentina, where Monsanto

ran an elaborate “bait-and-switch” to get the country hooked on its

genetically modified Roundup Ready soybeans before demanding royalties

on the crops that were by then already growing. DuPont then took over,

magnanimously beginning a “Protein for Life” programme to foist their own GM soybeans on the country’s poor.

The same scene has played itself

out in country after country, where cartel-developed GM crops are

foisted on emerging economies through “food aid,” usually during times

of famine when those countries are especially vulnerable. Only a handful

of countries like Zambia or Angola

have outright rejected this GMO takeover of their food supply,

generously subsidized by the US government to the benefit of the

agribusiness cartel.

Conclusion: Monopolizing Life

From cutthroat pioneers of the

early oil industry to Machiavellian social engineers and geopolitics

schemers, the oiligarchs have come a long way since the days of Devil

Bill’s snake oil cure-alls. But his use of every form of deception and

trickery to swindle the public informed how John D. and the rest of the

oiligarchs built up their business interests.

As the 20th century drew to a

close, it was obvious that for the powerful cartel that built the oil

industry–the Rockefellers, the Rothschilds, the British and Dutch royal

families–it was no longer about oil, if it ever really was. The takeover

of education, of medicine, of the monetary system, of the food supply

itself, showed that the aim was much greater than a mere oil monopoly:

it was the quest to monopolize all aspects of life. To erect the perfect

system of control over every aspect of society, every sector from which

any threat of competition to their power could emerge.

They had been remarkably, almost

unbelievably, successful. From oil well to gas pump, farm to fork,

hospital to pharmaceutical, drill rig to dollar bill, there was almost

no aspect of society that was not under control.

But the oiligarchs are not done

yet. Their next project, launched in the late 20th century, is almost

too ambitious to be comprehended. It is not about oil. It is not about

money. It is about the monopolization of life itself. They have spent

decades preparing the path for this takeover and marshaled their

mind-boggling resources in service of the task.

And the vast majority of the

world’s population, still playing the shell game that the oiligarchs

perfected and abandoned long ago, are about to fall right into their

hands yet again

www.corbettreport.com